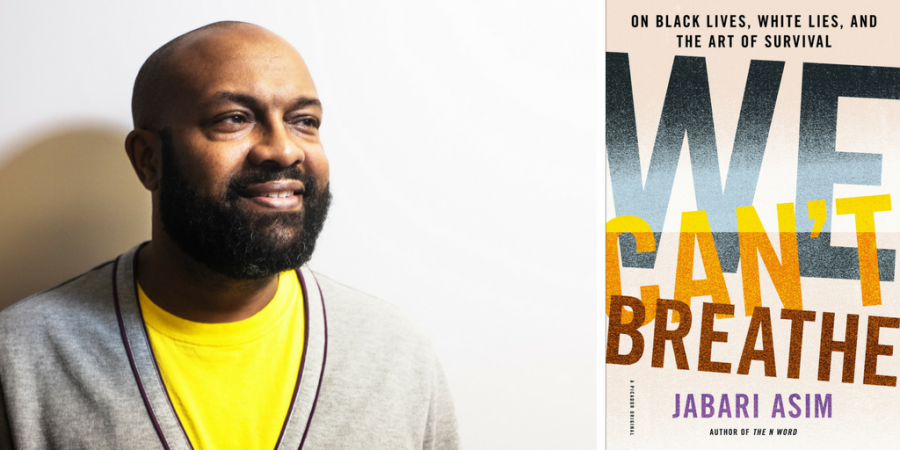

Jabari Asim discusses why “We Can’t Breathe”

November 29, 2018

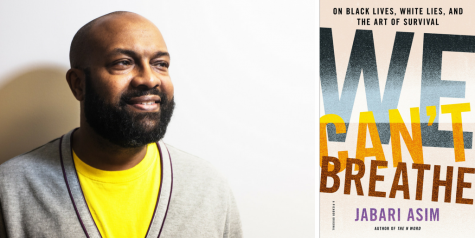

On the night of October 19th, I went into Harvard Square with high hopes for the evening. After meeting up with alumnus and former Eagle editor, Nicholas Fahy ‘18, and grabbing a quick slice of pizza at Pinocchio’s, I headed over to the Harvard Bookstore to hear from Jabari Asim, the author of eight essays compiled in his new book We Can’t Breathe.

The most intriguing aspect of his book listed online was its refreshing perspective on the African-American experience. In our classes at BC High, there is a great amount of focus on the political challenges faced by African-Americans, perhaps so much so that many kids might assume that their experience occurs in a vacuum and that once political equality was gained in 1964 with the Civil Rights Act, that their principal challenges vanished. But to name a few of the topics he addresses in his essays, there’s the “twisted legacy of jokes and falsehoods in black life; the importance of black fathers and community; the significance of black writers and stories; and the beauty and pain of the black body.”

The “talk” was actually more of a dialogue with Adrian Walker, a columnist at The Boston Globe. He read some key passages from his book and talked about how African-Americans have always been expected to love their oppressors in a way that asks them to “kiss the sword that has just sliced you open,” how being a white ally means using your whiteness to cause change from within, and how strategy is more effective at solving racial injustice than love.

Initially, these ideas seem radical to some white people. The truth is, there is no reason to feel guilty about anything that was presented unless you openly hold racist attitudes. On the first point, Mr. Asim, as a former political-columnist himself, pointed a lot of his comments towards the current presidential administration. The second point, he specifically asked that white people do not tell them about the many things that their racist cousin or uncle might say at Thanksgiving dinner— it is always the same negativity and ignorance— unless they mention how they told them just how wrong they were in response. Lastly, there have been proponents within the African-American community of taking the moral high ground and loving those who hate you, like Michelle Obama and, of course, Martin Luther King Jr.

That being said, Mr. Asim has a problem with the idea of having to be a “respectable” African-American to dispel racism. That is, by not confronting racists head on but instead hoping to prove them wrong by example of having a polite disposition and not sharing in aspects of African-American culture. While he called on the brainpower behind political and organizational strategy to solve issues of police brutality and wealth inequality that plagues African-Americans to date, he said that respectability and loving those who hate you is not a practicable solution. The latter part particularly struck me, because as a Catholic at a Jesuit school, I’ve been taught to love all of those and if I were to hate, then it would be to hate the sin and not the sinner. He quickly clarified that he still believed in love, but that solving these societal issues requires concrete problem-solving rather than platitudes, truisms, and words not backed by action.

There was a great diversity of people at his talk and the questions they had for Mr. Asim were just as poignant as the talk itself. An elderly African-American man, whom stated that he was once in the prison system, voiced his concern that the voices of the elderly and those adversely targeted by the “War on Drugs” in the 90s were being lost because of a rapidly changing culture. Although Mr. Asim said that he usually had literature to recommend people when it comes to various issues, that that was sorely missing amongst contemporary texts. A young lady wearing a hijab, likely a student at Harvard, asked how he made the transition from writing such heavy material to writing children’s books.

That question stuck with me because after learning about the Clark Doll Experiment in 1939, it left me thinking about what age children really start to become conscious of their own race and what role Mr. Asim felt he had in communicating messages to kids from a young age. While he simply said that his goal was to make kids happy, the thought lingered with me for a while after. Perhaps the question that left tangible tension in the room belonged to a middle-aged, white proprietor who asked what African-Americans would do if there were no white Americans.

Because of the vastness of this thought experiment, Mr. Asim responded that there was no way he could know personally what could happen. I think that white Americans have thought of hypotheticals like this because many are cognizant of the kind of pain that others have inflicted on people of color, yet it is an entirely inefficient thought to have because there is no realistic way this would happen to our society and it actually imposes guilt on all whites, including those who are allies whom have not only not harmed blacks, but have actively pursued positive institutional change for their interests.

Because of the vastness of this thought experiment, Mr. Asim responded that there was no way he could know personally what could happen. I think that white Americans have thought of hypotheticals like this because many are cognizant of the kind of pain that others have inflicted on people of color, yet it is an entirely inefficient thought to have because there is no realistic way this would happen to our society and it actually imposes guilt on all whites, including those who are allies whom have not only not harmed blacks, but have actively pursued positive institutional change for their interests.

Overall, I was very impressed by my experience at Harvard. I got a glimpse of just how diverse the academic world is outside of our little bubble on Morrissey Boulevard and felt that everybody was there to learn from each other, whom all had the credentials and experiences to back up their words. Although his signature of my copy of We Can’t Breathe says “To Dilly,” I’m already through one essay and would recommend reading it for a different perspective on race.